Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links. For more information, please visit our Disclaimer Page.

Smarter Faster Better

The Secret of Being Productive in Life and Business

Productivity is the process by which we look for a way to use energy, intelligence, and time to maximize results with minimal effort. We learn to succeed with the least stress and tension without sacrificing everything along the way that is dear and important to us.

We live in a world where all processes are simplified to the limit: colleagues are always in touch, important documents are stored on the phone, any information is available at the touch of a button, and goods are delivered to your home 24 hours a day. In theory, all these innovations are designed to make life easier, but work and stress only become more. We get hung up on tools (gadgets and applications) and forget that the most important thing is not the amount of information but how we process it. And yet some people managed to find a common language with the new world and turn the changes to their advantage.

From this summary of “Smarter Faster Better” by Charles Duhigg, you’ll learn how productivity works; how to set goals and priorities correctly; how to look at life in such a way as to see in difficulties, not problems but hidden opportunities; how to open consciousness to meet new creative achievements.

Motivation

Today, about a third of working Americans are freelancers, contractors, and people who somehow migrate towards free hire. They know how to motivate themselves, set the right goals, and manage their time competently. According to research, people capable of such self-organization earn more, feel happier and show more satisfaction with family, work, and life than their less collected comrades.

Fortunately, the ability to motivate yourself correctly is not an innate skill, but a skill, the same as reading and writing, which means it can be learned. Scientists have found that the main thing on this path is to maintain the belief that everything depends on yourself, that you are the master of the situation, and that you decide how your future life will develop. The need for control is a biological imperative and the key to self-motivation.

One of the ways to prove that the reins of power are in your hands is to make decisions more often. Any choice, even a small one, increases the sense of control and self-confidence.

That is why companies providing various services ask many questions when subscribing. Do you prefer a paper invoice or an electronic check? Tariff “Super” or “Super+”? One cable channel or another? The more decisions you make, the higher the probability of buying because as long as control is supposedly in your hands, you will play along with anything.

This is a good lesson for anyone who wants to motivate themselves to an action that initially causes resistance. As soon as you find the opportunity to make any decision regarding a particular situation, you will immediately feel able to control it.

For example, if you can’t bring yourself to sit down at a computer and parse your email, decide to respond to one randomly selected email. If you have an unpleasant conversation with a colleague, choose where the meeting will occur. If you’re a sales manager and it’s hard to start your next call, decide which question you ask first. What you choose matters far less than the action itself.

Another way to motivate yourself to an unpleasant action is to ask yourself, “Why?” always. So you will always keep the big picture in front of your eyes. I need to call a nasty colleague. What for? To get the job done. Why would I do this job? To support a family. Once a small step takes on a big goal, it becomes much easier.

Team

Over time, every group develops collective norms of behavior. Norms are the traditions, behavioral standards, and unwritten rules that govern our interactions. In one team, the norm may be to avoid disagreement intentionally. On the contrary, differences of opinion will only be encouraged. People may behave very differently as individuals, but general norms precede individuality within a group.

Group norms are key to how comfortable people feel within a community. For example, if it is customary for a team to fight for leadership, measure knowledge and criticize each other, most of its members will experience constant stress.

From the point of view of norms, the most successful teams function as follows:

• Leaders encourage others to express their points of view;

• Team members understand that they can show each other their vulnerability;

• Initiatives and mistakes are not punishable;

• Too harsh judgments are discouraged.

The above creates a sense of community and support in people but simultaneously pushes them to action. This condition is called “psychological safety.” In an atmosphere of psychological safety, team members understand that their “pack” is a safe place to take risks. They are confident that other group members will not condemn, reject or punish them for expressing the opposite point of view. The main values of such a team are trust and mutual respect.

To create an atmosphere of psychological safety, it is important to observe two basic conditions:

- All group members should have an equal opportunity to express their points of view.

- Group members should listen to the emotional state of others.

All other beliefs, such as “for a team to be effective, its members must be friends,” “the composition is of paramount importance,” “you can not do without a superstar,” and “you can not manage a sales team in the same way as a development team,” “the best teams in everything reach full agreement,” “to work smoothly, all team members must physically be in one place” and so on are nothing more than myths.

According to the researchers, group members do not need to be friends for effective work. It is only important that they listen to each other’s feelings and each has an equal opportunity to speak. How a group works is far more important than its composition. A team may consist of ordinary people, but if you train them to interact properly, a group of middlings will achieve more than any superstar.

Here are five key norms that increase overall effectiveness:

- Team members believe that their work as a group matters.

- Team members believe that their individual contribution to the work of the group matters;

- The team has clear goals and a clear distribution of roles;

- Team members know that they can rely on each other;

- An atmosphere of psychological safety is maintained in the team.

It is also important to remember that the team leader is responsible for the team’s culture, which is always one of the most difficult tasks for the leader. From the point of view of short-term effectiveness, it is easier to interrupt the argument, listen only to the one who understands the subject better than others and make a quick one-man decision. However, such “efficiency” undermines the atmosphere of psychological safety and negatively affects the group’s work.

Focus of Attention

Automation has penetrated almost all spheres of life: machines cope with a slippery road, answer customer questions, and finish offers for us. On the one hand, this greatly facilitates life, and on the other hand, it creates many problems because the more automated the environment becomes, the worse we manage our own attention.

The focus of attention is similar to a pocket flashlight – its beam can be wide and diffused or narrow and bright. In a normal situation, we keep the beam under control and decide which mode to choose. However, when a mechanical autopilot is nearby, we allow ourselves to relax completely, and the beam goes into wandering mode.

On the one hand, this is good: the brain saves energy by closely observing the environment and directing it to solve other problems. On the other hand, when some unscheduled event occurs – an unexpected email arrives, a sudden question arrives at a meeting – we get lost. Obeying the basic instinct, the brain concentrates on the brightest stimulus right in front of the eyes, but this is not always the right decision. When we are forced to abruptly switch from the state of autopilot to the panic concentration mode, a mental failure occurs, the so-called “cognitive tunnel .”Once in the tunnel, we immediately lose control.

A striking example is the crash of a Boeing 447, which performed a direct flight from Rio de Janeiro to Paris. The pilot was so confused by the emergency situation (which could have been quickly resolved) that he concentrated all his attention on the panel before his eyes and did not notice other signals. Instead of calmly assessing the situation and making an informed decision, he repeated the same action, although it did not bring any result and only aggravated the situation. After four hours on autopilot, his brain relaxed so much that from panic, it entered a cognitive tunnel, a kind of peak, resulting in people dying.

The closest neighbor of the cognitive tunnel is reactive thinking. When we panic and stop thinking clearly, the brain reproduces the most familiar sequence of actions. In many life situations, this function is beneficial: athletes especially hone movements and bring them to automatism, so the “body” reacts faster than conscious thought during the game.

The downside of reactive thinking is that habits and automatism can outweigh common sense.

If you have never lost in your head the scenario of skidding the car and did not remember that the steering wheel needs to be turned in the direction of the skid, then on the road, you will act reactively, i.e., turn the steering wheel against the skid, and this can cost you your life.

Mental models of reality help to better manage attention. Mental models are a sieve through which we sift through the incoming flow of information and which helps us choose where to direct the ray of attention. We all tell ourselves stories about how the world works, draw pictures of what we expect to see, talk about what this or that event means, mentally replay upcoming conversations, and so on.

That is, we transform experience into a narrative. The more often you do this and the more parts your model has, the more stable it is. And the more stable the model, the easier it will be for you to navigate the real situation and understand what went wrong and how to fix it.

Objectives

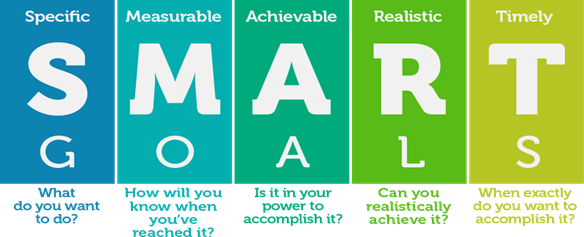

In the 1940s, representatives of the General Electric Company formulated a system of goal setting, which would later become known worldwide under the abbreviation SMART. According to this system, the goals should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Timeline. In other words, the goal should be objectively achievable, and you should have a specific plan to achieve it.

Smart-system is effective for two reasons:

- It makes it necessary to transform vague perspectives into a concrete plan of action (and the smaller the step, the more likely that the final goal will be achieved);

- Specific deadlines encourage self-discipline, which is impossible to achieve in conditions of uncertainty.

However, this technique has its drawbacks. In the pursuit of productivity, we are often carried away by formalities: all the steps to achieve the goal meet smart criteria, but the goal itself is so trivial that it simply does not make sense. In addition, we tend to focus on simpler tasks and usually try to complete the project at all costs. Evolutionarily, the brain is focused on making decisions and backs them up with happiness hormones. However, a decision made only to “close the gestalt” is not necessarily correct, and the to-do list has become one point smaller. This does not mean that the action originally made sense.

To avoid falling into the loop of cognitive closure, when the decision itself becomes more important than its quality, it is necessary to have a more global goal in front of you. It’s okay if you do not know how to achieve it at the time of production. It’s even welcome. The main thing is to observe a fine line: the goal should be complex but still doable.

Thus, the goal-setting process consists of two stages:

- First, you need to set a global goal. It should be ambitious and complex but doable and reflect the general values of life.

- You need to break down the process of achieving it into many small sub-goals that meet the SMART criteria. Great goals are useless if not backed up by a concrete action plan.

- Manage others

In 1994-1995, two teachers of the Stanford Business School launched a study on the problem of corporate culture. Their goal was to determine whether management builds hiring policies, how it treats its employees, and what culture of interaction it instills in them, which plays a decisive role in the company’s success in the long term. For 15 years, James Baron and Michael Hannan collected data on thousands of Silicon Valley companies.

According to the results of the study, they identified five main models for building a corporate culture:

- Star – Management hires employees from elite universities or successful companies, giving them almost complete autonomy.

- Centrist engineering – there aren’t many individual stars in the company; rather, engineers rule the roost as a class (e.g., Facebook).

- Bureaucratic – all the emphasis is on middle managers. Every process within the company is recorded, and meetings become a ritual.

- Autocratic – very similar to the bureaucratic model, the only difference being that all protocols and rituals aim to satisfy one person’s desires and goals, usually the CEO.

- Loyal – this model ensures that employees leave the company no earlier than they want to retire. Management believes that building the right corporate culture is more important than creating an ideal product (and therefore, in difficult times, they are more likely to invite another HR specialist than to dismiss ordinary employees or hire more engineers).

The last model was especially characteristic of companies of the middle of the last century when working all their lives in one place was considered honorable. With the advent of the era of technology startups, a loyal culture began to be perceived as a relic of the past – such companies are considered too slow and clumsy.

But as it turned out, it is the loyal model of corporate culture that most correlates with success. Star teams, as a rule, showed excellent short-term results – smart people quickly began to earn, but in the long term, such companies were the least likely to reach the IPO stage. The team was constantly torn by internal conflicts- unsurprising – where everyone claims to be the biggest star, a fierce competition is inevitable.

The researchers found that none of the companies built on the loyalty model failed over time. On the contrary, loyal companies were the fastest to go public, had the highest profitability ratios, and were more flexible than their competitors. They had the thinnest layer of middle managers, which is also unsurprising. Since they are usually in no hurry to hire new employees, HR specialists have time to choose the most collected and internally motivated people. Loyal companies knew their customers better and reacted the fastest to market changes.

But the main thing is that the trust between employees, managers, and customers was so great that it motivated everyone to work even harder. A loyal environment helps people not to give up their business and support each other even in the most difficult times.

Loyal companies fire employees only if there is simply no other way out. They invest in the education and development of their employees. They strive to maintain an atmosphere of psychological safety. They know a business’s biggest losses are when an employee leaves for a competitor, taking the accumulated knowledge and customer base.

Solutions

The ability to make the right decisions directly depends on correctly predicting the future. However, this process is not easy for us, as it forces us to admit how much we do not yet know and can not foresee. Paradox: To learn how to make better decisions, we must accept uncertainty. And for this, you need to learn how to imagine the future and its options differently.

Usually, we try to make a decision based on binary probability: it will either be so or another. Intuitively choose the most likely option, and try to justify it logically. But the world is more complicated. Every situation has a lot of outcomes, and each has a different probability of coming to fruition, which means that the future isn’t the only possible outcome. Still, many outcomes contradict each other until one comes to a realization.

Probabilistic thinking is the ability to hold in your head a lot of contradictory outcomes and assess their relative probability. This thinking distinguishes the hope for a certain outcome from the actual probability.

It is noteworthy that sometimes we can correctly predict the situation’s development even in the incomplete absence of introductory ones. In the late 1990s, MIT cognitive science professor Joshua Tenenbaum wondered why we were so good at predicting certain events when we knew virtually nothing about all the potential circumstances. He conducted a large-scale study and found that most people intuitively understand that different assessment systems are needed to predict various events.

Tenenbaum asked students to predict the future based on the minimum number of inputs:

1) how much the film will collect at the box office if by now it has collected 60 million dollars, and

2) if the person is now 39 years old, how much he or she has left to live? The participants’ predictions were surprisingly accurate. They understood that a film that had already collected 60 million was likely a blockbuster, meaning it could gain another 30 million.

Both predictions were made based on different assumptions, but only a few participants could describe the logic used in the decision-making process.

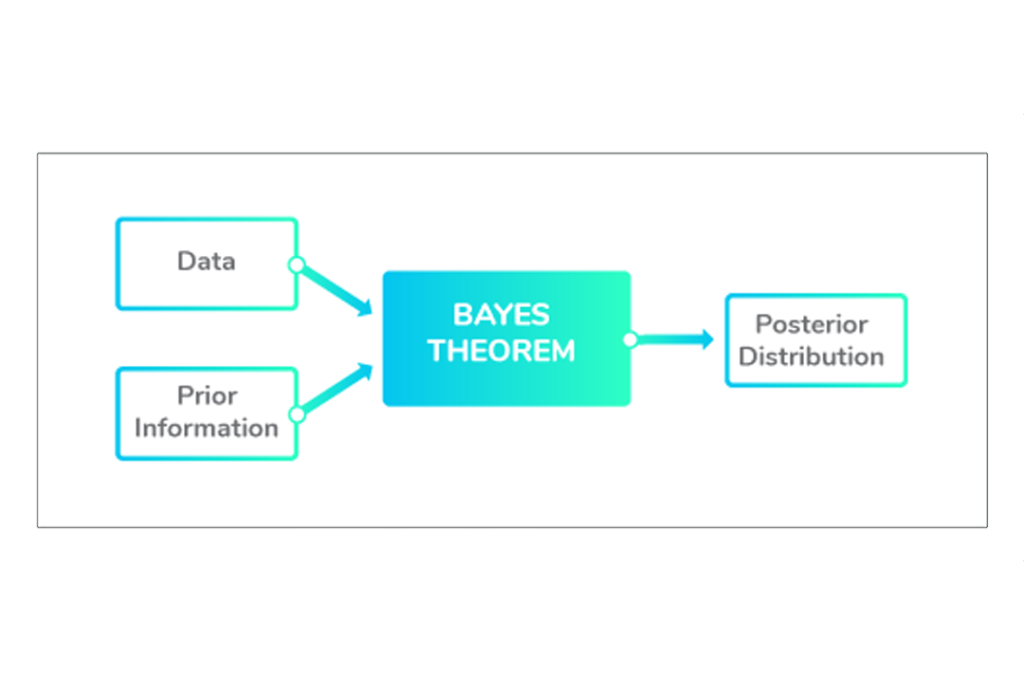

The ability to intuitively grasp patterns is called “Bayesian thinking.” Bayes’ rule is based on the following principle: even with a very small amount of data, forecasting the future is possible – you need to adjust the assumptions in accordance with the incoming information constantly.

For example, a brother says he is meeting with a friend in the evening. Most of his friends are men, so you assume he will date a man with a 60 percent chance. During the further conversation, it turns out that the friend is a colleague at work. You immediately adjust your prognosis because most of your brother’s colleagues are women. Bayes’ rule allows you to predict based on the minimum amount of information. The more data, the more accurate the forecast.

Now the Bayes mechanism is the basis of computer forecasting, and people make such calculations almost without thinking. However, the system only works if the original assumption is correct.

When Tenenbaum asked the study participants to predict how long a pharaoh who has ruled for 11 years would have to reign, most of the students were wrong: they framed the well-known formula of European kings – if a king lives to middle age, he will rule until he dies – and on average predicted the pharaoh would be another 23 years on the throne. However, life expectancy in ancient Egypt was much less than in the Middle Ages (people of thirty-five were considered almost old people), meaning that the pharaoh had to rule for a maximum of 12 years.

For the initial assumptions to be correct more often, expanding and constantly updating the experience obtained is necessary. All our beliefs are based in one way or another on past experience, but the final sample often does not coincide with reality.

For example, we tend to remember successes and forget failures. We read the stories of successful businessmen, go to famous restaurants and watch popular movies. The problem is that in this way, we get acquainted with only one – successful – side of the field of activity. And since we see only success, we predict it more often than failure. The hope for a certain outcome wins over the actual probability.

On the contrary, successful people look for information about failures and failures because the more victories and disappointments are taken into account, the more accurate the forecast is.

Innovation

Today, in the context of the deadline economy, the ability to come up with quick and non-standard solutions is one of the key ones. We can no longer afford to swing for a long time, creative search should be as productive as possible.

The classic method of speeding up the creative process is to take time-tested ideas and combine them with each other in a new way. The main factor influencing the audience is not the idea but how you initially combined the existing knowledge.

An excellent example of an unusual combination of familiar ideas is social networks. The programmers took a model to explain the spread of viruses and extrapolated it to how we share the news with friends online. Most of Edison’s inventions also import ideas from one science to another. Even in the financial sphere, the price of stock derivatives is calculated using a combination of a formula describing the movement of dust grains and techniques from the field of gambling.

Many “geniuses” are intellectual intermediaries who have mastered transferring knowledge from one area to another. In sociology, they are called “innovation brokers .”Brokers often act as a link between different social groups. They’re more likely to express their ideas, and society is more likely to accept them because brokers make an ironclad argument: the idea has already worked elsewhere. Hence, creativity is not a lot of geniuses but a well-established import-export activity.

Remarkably, a brokerage is not directly related to personality type. Studies show that anyone learning to analyze his experience qualitatively can become a broker. As we age, we get used to not paying attention to our emotions and forget that feelings are wonderful creative material. To connect the knowledge we already have and synthesize something new, we must reflect more than usual on the experience gained.

It is believed that the main enemies of creativity are panic and stress. However, this is not entirely true: the brain sometimes works more sharply in an inflated state. Psychologists call this condition “productive despair.” Studies by cognitive psychologist Gary Klein confirm that in 20% of cases, creative discoveries were preceded by anxiety and stress.

For example, when the Disney team worked on the cartoon “Frozen,” no one expected that the holding would be forced to shift the deadline for the project. The team had to show the current version of the script urgently, and it turned out that it was no good. All participants were extremely stressed for a long time, as they could not move from the dead center. However, in the conditions of a hard deadline, you do not have a choice: the situation forces you to look for non-standard approaches. Disney animators decided to replay the standard template of the cartoon about the princess and rely on their own feelings and experiences. As a result, “Frozen” broke all records of popularity and became the highest-grossing cartoon in the history of Disney.

Small perturbations also benefit creativity. In biology, this is called the “moderate destruction hypothesis.” Biodiversity reaches its peak in conditions of moderate destruction: a tree that has fallen in the Amazon forest creates an empty space where sunlight suddenly penetrates, and new species enter the struggle for existence in the old range. Where nothing like this happens, sooner or later, there comes a stage of “competitive exclusion” – one species becomes dominant and displaces competitors.

Within the theory of creativity framework, this means that if you or your team feel that after a strong rise, you are again trampling on the spot, make small changes within the system, and the process will continue.

For example, after the creators of Frozen turned to their own emotions, things went so well that at a certain point, they again found themselves at a dead end: they had too many good ideas, and they had to choose something, give up something, but no one could make this decision. Then the management appointed the screenwriter of the film as a co-director. Seemingly insignificant changes moved the team forward again. After becoming a director, the writer had to change the angle of view, and this small shake was enough for her to cut off the excess, and the rest agreed with her.

Creativity cannot be reduced to a clear formula, but the creative process is in our hands. If you want to become a creative broker, then:

• listen more to your own experiences;

• realize that anxiety and stress are an opportunity to see the old in a new way and not a sure sign that life is going downhill;

• Remember that a creative breakthrough can be blinding – don’t be afraid of bumps on the road, and keep your distance about your creation.

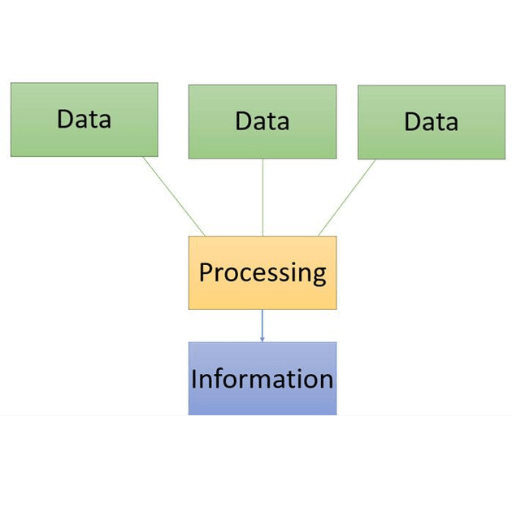

Data Processing

With the advent of the Internet, the search for an answer to any question of interest to us began to take no more than a couple of minutes. But finding an answer and understanding what it means are completely different things. The amount of information available has increased significantly, but our ability to process it has remained unchanged.

In theory, the information boom should have simplified the decision-making process, but in practice, a huge number of inputs not only does not facilitate but, instead, complicates the choice. When there is too much data, we lose the ability to use it and fall into networks of “information blindness”: we ignore certain options or refuse to work with incoming information altogether.

To process information efficiently, the brain fragments and categorizes it. The result is like a file system that helps you store and quickly find the data you need.

For example, if a restaurant brings you a huge wine list, the brain will find the “Wine” compartment and help you choose, moving from general categories to private ones with the help of binary alternatives. White or red? White. Expensive or cheap? Brummagem. Sauvignon for $7 or Chardonnay for $6? Drawing on past experience, Chardonnay. The brain performs these operations so quickly that we are often unaware of them.

This is how abstract information turns into knowledge. The brain always tends to reduce the choice to two, a maximum of three options. If there are no files on some issue, the brain again turns to the binary decision-making scheme in the most general form: should I understand this stream, or is it so difficult that it is better to postpone? Then it all depends on the motivation.

One of the ways to overcome information blindness is to break down data into small fragments and force yourself to make decisions for the smallest reasons. Instead of choosing homemade wine in a café out of habit, you have to try to ask yourself a series of questions: red or white, dry or sweet, and so on. You need to put obstacles in your way consciously.

For example, to force yourself not just to read but to realize and remember a boring instruction, you can print it in a hard-to-read font: the more difficult it is to process the text, the more you think about what you read, meaning you remember better. Recording lectures by hand is harder and longer than typing on a computer, but those who write by hand usually get higher grades — the more time-consuming the processing process, the more we can extract from it.

People should actively interact with information. If subordinates do not perceive all sorts of work memorandums and instructions well, invite them to independently develop several hypotheses about how everything should work or how to solve a particular problem and ask to support the theory with practical data.

This approach combines information fragmentation tactics and the “engineering design process.” An engineering design process is a methodical approach to problem-solving. This system requires employees to identify a dilemma, collect the necessary data, brainstorm possible solutions, discuss alternative approaches, and conduct multiple experiments. It helps with any, even the most difficult tasks. A person has to simplify the problem until all its fragments are sorted into appropriate folders.

Passive consumption of the incoming stream does not give such an effect: abstract information remains outside the file system, which means that it never passes into the category of practical knowledge.

Conclusion

Productivity is not a destination but a process. It depends on what decisions we make at any given time. Productive people force themselves to make decisions that others ignore.

If you can’t get started on an unpleasant task, choose what makes you feel like the master of the situation. Feeling that you control the situation will significantly increase the chances of success. In addition, any decision is a reflection of your values. By answering the question “Why?”, you remind yourself that the current task is only a step towards a global goal.

Goals are of two types: global and specific. Their combination gives the maximum effect. To begin with, determine the main life aspirations and then write down each of them, relying on the SMART system: the sub-goals should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and limited in time.

To maintain the focus of attention and not be distracted from the goal, we are helped by mental models – mental stories about what we expect to see. Before completing a task from the SMART list, imagine what exactly you will do and how you will react if something goes wrong. The more details you can imagine, the better.

When something goes wrong, imagine the different scenarios in the future, then analyze which ones seem most likely to you and why. To make the best decision, do not abandon contradictory scenarios. The more options, the higher the likelihood that you will be able to make the right choice. Hone your Bayesian instinct — strive for new experiences. So you can more accurately make even “subconscious” assumptions.

The most important thing in the team’s work is the atmosphere of psychological safety, based on two concepts:

1) everyone should have an equal right to vote, and

2) colleagues should pay attention to each other’s feelings and thoughts. The responsibility for the proper atmosphere always lies with the manager.

Innovation results from a creative process in which old ideas acquire new potential. Innovation brokers play a key role in this process. To become a broker, you must be sensitive to your own experiences, perceive stress as an opportunity to make a breakthrough, and not allow yourself to get too carried away with the object of creation, not to lose clarity of view and the ability to see alternatives.

Actively work with information. The more difficult it is for you to perceive it, the more likely it is that, in the end, it will turn from abstract data into practical knowledge. Fragment the incoming stream: the smaller the pieces of information you perceive, the more folders and subfolders your file system will contain and the easier it will be for you to navigate.

F.A.Q. about “Smarter Faster Better” by Charles Duhigg

What is “Smarter Faster Better” by Charles Duhigg?

“Smarter Faster Better” is a non-fiction book by Charles Duhigg, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist. The book delves into the science of productivity and examines why certain individuals and businesses achieve greater success than others. By presenting real-life examples and scientific research, Duhigg provides practical guidance on how to boost productivity in both personal and professional domains.

What are the main themes in “Smarter Faster Better”?

“Smarter Faster Better” explores themes such as the importance of habits and ways of thinking in achieving success, effective motivation strategies, setting challenging yet achievable goals, and the role of teamwork and communication in achieving success.

What are some key takeaways from “Smarter Faster Better”?

“Smarter Faster Better” offers several key takeaways. These include the significance of creating mental models to understand the world better, setting stretch goals to increase motivation and productivity, focusing on the process and using feedback to improve performance and adopting a growth mindset to believe that abilities can be developed through hard work.

Who should read “Smarter Faster Better”?

“Smarter Faster Better” is a helpful book for anyone seeking to increase their productivity and success. It is particularly useful for professionals aiming to enhance workplace efficiency, but its principles can also be applied to managing personal tasks and hobbies. The book is suitable for readers of all backgrounds and experience levels.

Quotes from “Smarter Faster Better”

“Productivity is about recognizing choices that other people often overlook. It’s about making certain decisions in certain ways.”

“To be effective, people also need to have a clear sense of their goals, and they need to believe that they’re capable of achieving those goals.”

“When people are given a menu of choices, they’re more likely to make a choice, and more satisfied with the outcome.”

“Motivation is triggered by making choices that demonstrate to ourselves that we are in control.”

“One reason that timing works as well as it does is that it’s such a simple and powerful way of making people feel that they’re in control.”

“To-do lists are useful mainly as a reminder of what we want to accomplish. But they’re less effective for the actual planning of our time.”

“The most productive people we’ve interviewed don’t necessarily work longer hours than everyone else, but they do work much more intensely during those hours.”

“The most successful people I know – both financially and in other ways – are shockingly helpful. They’re incredibly good at understanding other people and helping them achieve their goals. They know their success is ultimately based on the success of the people around them.”

Disclaimer: This blog post is a summary or resume of the book and is not intended to dispense the reading of the original book. This post aims to provide a general overview of the book’s main ideas and themes and encourage readers to read the complete book to gain a deeper understanding of the material. The information presented in this post is intended to be something other than a substitute for the original book and should be used as a supplement to, not a replacement for, the entire book. We strongly encourage readers to read the complete book to benefit from its ideas and teachings fully.